1993, 200 minutes

Released to mark 100 years of women's suffrage in New Zealand, Bread & Roses tells the story of pioneering trade unionist, politician and feminist Sonja Davies (1923 - 2005) who rose to prominence in the 1940's and 50's. At over three hours in length, it was created for a dual cinema/television release.

“In the ‘kill to watch’ category …faultlessly directed”

Selected: New Zealand, Melbourne, San Francisco, Brisbane, Perth, Toronto, Seattle, London

You can buy / rent it online:

ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT - Neil Jillett

SPLENDID PICOT SETS NEW STANDARDS

It may be a parochial point to make about a 'foreign' film, but it is impossible to ignore. In the central role of the New Zealand drama Bread and Roses, the Melbourne actor Genevieve Picot gives probably the finest screen performance ever by an Australian woman. She has been provided with a great story and a fine script, and she makes the most of them.

Bread and Roses is a two-part tele-drama that is deservedly being screened as a 196-minute feature. Don't be put off by the length; this film never drags. It is directed and co-written by Gaylene Preston, although the main writing credit goes to Graeme Tetley. He and Preston collaborated on the sprightly generation-gap comedy Ruby and Rata, which inexplicably did not get a commercial release here after its success at the 1991 Melbourne Film Festival.

Their new film is based on the autobiography of Sonja Davies, feminist, socialist, pacifist, trade unionist, politician, justice of the peace, anti-nuclear campaigner, marriage celebrant, farmer, nurse, wife, mother and general stirrer. Bread and Roses does not tell her whole story (she is still alive) but concentrates on events between 1942, when she made a short, disastrous marriage at the age of 17, to her first move, 40 years late, into the limelight of national fame and notoriety. The only things seriously wrong with Bread and Roses are its opening and closing minutes. The first few scenes are clogged with didactic, overloaded dialogue. The last scenes, though theoretically well-chosen to close the film on a high note, are handled with a disconcerting abruptness. But my complaint about this ending is partly a tribute to Preston and her colleagues. They had presented most of the drama with such entertaining intelligence that I wanted more of it.

The chief beauty of the script is the naturalness with which it links political events and everyday domestic reality. These events are not always of much public significance, but they are always stamped with interest because of Sonja Davies' stubborn enthusiasm.

But Sonja was far more than a woman with a soapbox. She was born out of wedlock and had her own first child while she was single. This double whammy of 'illegitimacy' led to a fascinating love-hate relationship with her mother (played with sulky yet touching primness by Donna Akersten). Sonja contracted tuberculosis while she was a nurse, and her battle against the disease, which nearly killed her, is a big part of the drama. Her second marriage, to Charlie (Mick Rose), was happy – and provides more drama. Charlie's exasperated geniality, his acceptance of the role of second fiddle in their family, gives Bread and Roses a firmly comic underpinning.

Picot (Sonja) is almost as convincing as a 17-year-old, and thoroughly convincing at all other ages. The script gives her plenty of opportunities to show her range – Sonja coughing blood, enduring a long labour, smugly or proudly standing up for her beliefs, muddling through a driving lesson, getting an ironic pleasure from being an efficient housewife, berating men for their blindness. Picot gives us the whole woman, self-righteous and arrogant as well as altruistic and compassionate. There is a fierce glow to Picot's performance that never lets us seriously question the truth of the life she is recreating or the integrity of the woman who lived it.

It is a mark of Picot's professionalism that, unlike some New Zealand members of the cast, she gets the Kiwi accent of the times right. And, apart from a few lapses, the film looks unostentatiously in period, thanks largely to Rick Kofoed's design and Allen Guilford's photography.

ILLUSIONS MAGAZINE - Helen Martin

Issue 23, Winter 1994

'As we go marching, marching in the beauty of the day A million darkened kitchens, a thousand mill lofts gray Are touched with all the radiance that a sudden sun discloses For the people hear us singing: Bread and roses! Bread and roses!'

So goes the first verse of the poem written by James Oppenheim, then set to music by Caroline Kohlsaat, from which Sonja Davies borrowed the title of her autobiography. The poem was written in celebration of a spontaneous walkout stage in Massachusetts in 1912 by some 20,000 mill workers. Protesting at pay cuts to be brought about by a reduction in maximum working hours for women and minors employed at the mills, many of the young women carried banners declaring 'We want bread and roses too'.

Of course the idea that having a full stomach is only half the equation vis a vis the quality of life is also biblical ('And when the tempter came to him, he said: If thou be the Son of God, command that these stones be made bread. But he answered and said, It is written, Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceedeth out of the mouth of God' ' ). So there's irony in the way the original intentions of the metaphor are scrambled in the NZ on Air Bread and Roses advertisement that appeared in The NZ Listener (October 18, Page 68) headed with the caption 'One cannot live by bread alone', illustrated by a photograph of a bunch of red roses stuck in a bowl containing a goldfish (the NZ on Air logo) and containing the praise of 'a critically acclaimed series to enhance your staple TV diet'. But then, in a deregulated economy and with market forces rampant anything goes when there's a product to be shifted.

Still, you have to laugh, and it is possible that Sonja Davies would find amusement in the advertisement's appropriation and demeaning of the Bread and Roses title. Active in national politics until her retirement at the 1993 elections, she has seen a lot of changes in her lifetime, but she might find it hard to deny that the more things change the more they stay the same, market forces mentality included. Having begun her career as a nurse who wanted better working conditions for her profession, she now ends it with the nurses still on strike. Having spent her life working to promote humanist ideals' her television advertisement in support of the Labour Party in the leadup to the last election reveals the shock she felt when, on a recent admission to hospital, she found that, rather than being in a ward she was in a 'business management unit'.

As Nelson secretary of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in the early 1960s' Sonja Davies helped organise a petition seeking government support for a ban on nuclear weapons. In the self-effacing tone that typifies how she describes her life, Davies writes in her autobiography:

'In those days I believed that thousands of signatures on a petition to Parliament could help change the hearts and minds of the politicians. What a naïve creature I was…' .

In charting her growth from ingénue to shrewd politician, Davies' storytelling style is plain, matter of fact and, most importantly, entirely without self-promotion. Bread and Roses, the autobiography, is fascinating not because of the style in which it is written, but because the content is so compelling. In a lifetime of commitment to improving living and working conditions for all people, with special interests in bettering the lives of women and in peace issues, just some of Davies' numerous achievements include founding the New Zealand Working Women's Council, membership of the Equal Opportunities Tribunal, having a Working Women's Charter accepted by the New Zealand Labour Party and by the Federation of Labour (of which she was the first woman vice-president), election to Parliament as the Labour member of Pencarrow and the role of Pacific representative on the World Peace Council. In 1987, Davies received the Order of New Zealand (the country's highest honour). Victoria University has awarded her an honorary Doctorate of Law. Made as a fourpart television series and also screened theatrically, Preston/Laing Productions' adaptation covers Sonja Davies' early years (she was born in November 1923) up until the beginning of her political career proper with her election on to the Nelson Hospital Board in 1956. The series is not the biography of the experienced politician at the peak of her powers. It is, rather, a distillation of the formative events – personal, local, national and international – that shape the young woman's developing political consciousness.

Growing up in a classconscious, sexist society, Sonja's personal experiences and her observations of the experiences of others lead her to develop early a strong socialist and feminist sensibility as, with no role models to guide her and with no sense of belonging, she quickly learns to rely on her own resources. Along with many joyful, life-enhancing experiences, Sonja suffers much sorrow and fear through separation, loneliness, loss, chronic illness and more than one early brush with death. Her story, then, has many layers and it is thanks to the imagination and intelligence of the Bread and Roses film makers and actors that this complex story is realised so evocatively on the screen.

Born illegitimate, Sonja spent her first seven years living with her much-loved grandmother before being taken to live with her mother and stepfather. In Episode One, two events from her early childhood economically sketch in two of the major themes in her life. The shot of Sonja's great-grandmother reading the small palm and predicting a lifetime of joy and sorrow points to the sense of destiny that runs through the narrative and that is reinforced throughout by Sonja's words and by repeated hand imagery, (Sonja's fists are clenched as she announces her intention to leave home, for example). The other is the young Sonja's reaction to her mother's patronising attitude to the working class woman to whom she dispenses charity. Sonja obviously identifies with the woman's anger and seems unconvinced by her mother's dictum that 'the unemployed are lazy and don't want to work'.

Brought up as a member of the middle-class, Sonja's empathy is always more with the working class. As a teenager, constant fights with her parents – her stepfather castigates Sonja and her 'Red Fed' friends for their pacifist views, her mother vets her 16th birthday party guest list to keep out the working class – drive her from the family home. Her growing interest in left wing politics, combined with alienation from her family (at whom she rages 'for the first time in my life I've found someone to belong to'), propel Sonja into a hasty marriage to one of the British upper class. Privileged as he is, he agrees with her hotly argued assertion that 'Capitalism is an international conspiracy of the upper class'. But Sonja's 'solution' to her loneliness is short-lived as, in a couple of economical scenes, the marriage crumbles (husband Lindsay Nathan extols the virtues of sexual adventure as opposed to the 'tyranny' of monogamy) and the couple are divorced. When Sonja goes nursing she continues to develop her political ideas through association with her conscientious objector friends and her convictions remain undented by the vilification of those supporting the war.

Her personal life is enhanced by warm friendships formed with other nurses although her left-wing convictions are a constant source of irritation to her roommate and best friend Con. For Con, politics are 'forbidden territory' while to Sonja there is 'nothing more important'. Class differences are seen in Con's hopes to find a boyfriend who's a colonel, while Sonja wants someone 'from the ranks'. Although Sonja has an understanding of sorts with Charlie Davies, a left-wing friend currently serving in the army service corps as a non-combatant, all thoughts of him are swept away when she becomes passionately involved with an American soldier, Red Brinsen. As Episode One ends, with Sonja still arguing with her stepfather over the ethics of war and peace, she confides in Con that she is pregnant.

With Sonja's interest in global and national politics thus established, her political consciousness is further raised in Episode Two where the focus shifts to her personal experiences of injustice. Firstly, she is threatened with expulsion from the nursing profession when poor working conditions lead her to express interest in finding out from Trades Hall how to establish a nurses' union. Told by Matron that 'Nursing is a profession … not a trade' and that 'Nurses are not factory girls'. She is further disillusioned to find that her fellow nurses are not prepared to support her.

When her mother, terrified of displeasing her judgmental husband, refuses to support her in pregnancy, Sonja goes to stay with pacifist friends in the country. There, miners on strike to persuade their bosses to provide a concrete floor remind Sonja that nurses are not the only workers in need of better working conditions. Forced to have her baby alone in a bleak, impersonal hospital Sonja experiences for the first time the grimness of the medical profession from a patient's point of view. When Red's money ceases coming she moves back home with daughter Penny and plans to go back to nursing.

She celebrates the end of the war with her old nursing friends then learns she is unable to go back to work because the tuberculosis she contracted while nursing, due to the negligence of the hospital administrators, has become serious. At the end of the episode, Sonja finds a minder for Penny and goes to hospital.

For much of Episode Three Sonja is critically ill in hospital. Her will to live waivers when she learns of Red's death in the Pacific but she rallies and resolves to fight her illness when she hears two nurses casually discussing her poor prognosis as though she is a piece of meat. Back in the hospital where she trained, she finds support from the women who nursed with her and from Charlie Davies but the insensitivity of the doctors is a constant source of anguish and the difficulty of finding childcare continues. Released from hospital she retrieves Penny and marries Charlie and they go to live in the country where they meet up with other like-minded people. With only half a lung Sonja fights the government to win the rehab loan to which Charlie is entitled but that struggle, combined with the harsh, primitive conditions under which they are living causes a relapse and Sonja is forced to spend nine more months in hospital. Thanks to a new drug she is finally cured and the Davies decide to leave the farm.

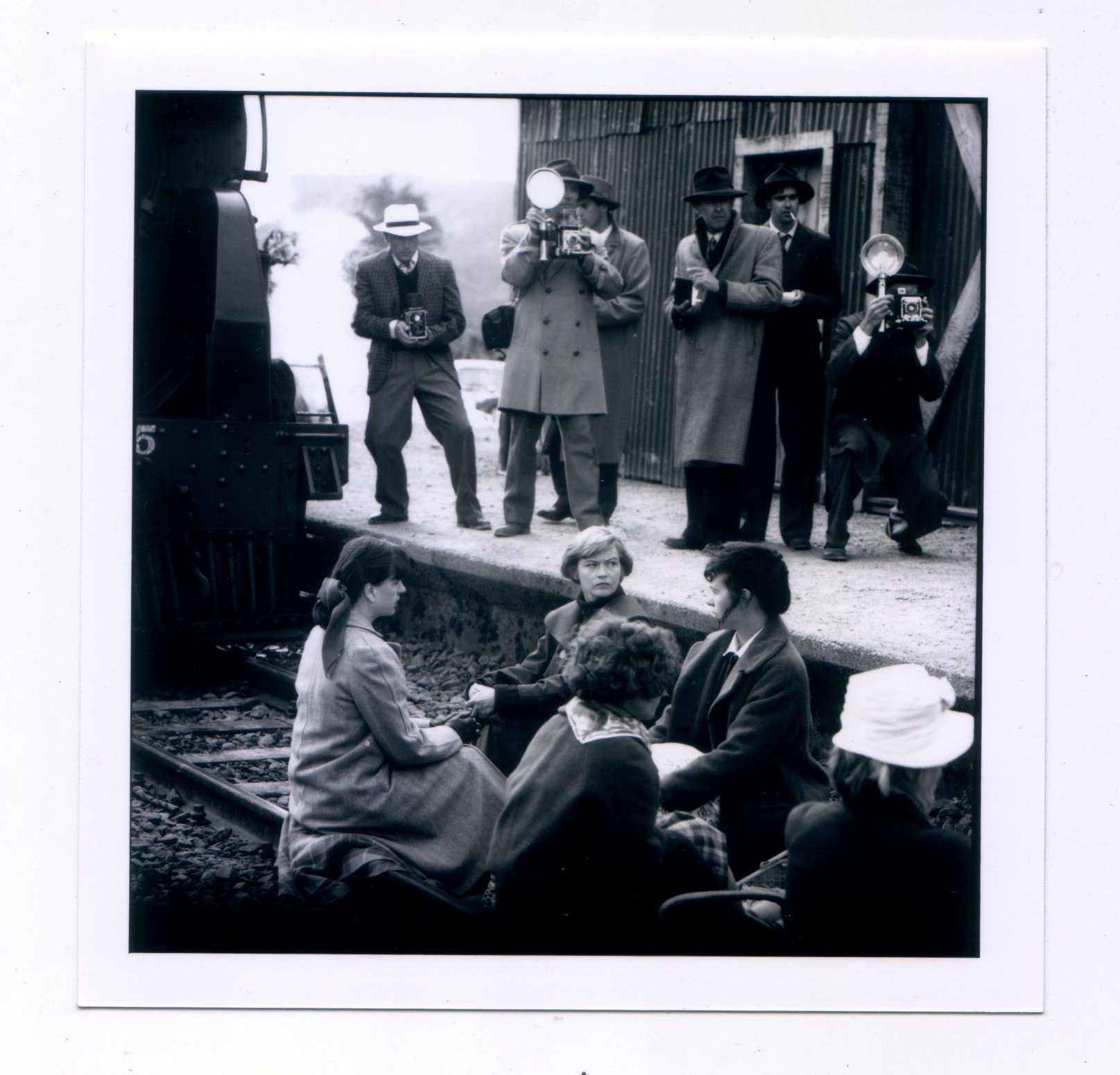

Episode Four sees Sonja on her way as an active participant in the political life of the country. Her readiness to put her illness behind her is signalled by a brilliant opening sequence which begins with a closeup of a dripping tap then pulls back for a shot of Sonja disconsolately washing dishes at the kitchen sink, while on the radio Aunt Daisy breathlessly informs listeners that after she's given out her beetroot chutney recipe she'll be playing the scrapbook piece Married Life. A number of scenes depicting Sonja's efforts to gain nomination for an office within the Nelson Labour Party show that much of the opposition comes from men who think she should be at home caring for her 'other responsibilities'. The chance for real political action comes when Sonja joins a group of women who try to prevent the closure of the Nelson railway line by a campaign of civil disobedience. This action, although unsuccessful in its objective, results in Sonja's nomination as a member of the Nelson Hospital Board. Realising she needs to be independent Sonja begins learning to drive. She tells Charlie she is pregnant. After she has given her speech to the Hospital Board selection committee Sonja walks from the building past bushes of red roses. She tells Charlie, who is waiting for her, that, due to factional squabbles, she has been elected to the board as the deputy chairman, takes up her position in the driver's seat of the family car and, as she drives away past more rose bushes, they laugh about the capriciousness of politics.

As both evocation and documentation of Sonja Davies' formative years the Bread and Roses script (co-written by Graeme Tetley and series director Gaylene Preston) shapes its carefully selected incidents and events to convey the character and development of its protagonist with a sharp focus. Full of sentiment without being sentimental, the series stands as a tribute to a most remarkable woman without presenting her as a saint.

Her bluntness often looks like tactlessness, she is impatient with opposing views and, as her political career starts rolling, daughter Penny often seems to be futilely waving for attention from the sideline. It is to the credit of Australian actor Genevieve Picot, with her excellent timing and with her understanding of the character conveyed in every glance, word, movement and gesture, that the character is portrayed so superbly. A very competent (and at times inspired) supporting cast contributes to the drama's credibility.

Bread and Roses is equally fascinating as a social history. Sexual politics, where matters concerning the role and position of women as workers, friends, partners, child bearers and child minders are woven seamlessly into the narrative, as are issues of class and privilege, politics and power. But all this is achieved with a lightness of touch that ensures the drama never becomes didactic. In the hospital scenes, for example, a wry kind of bed-pan humour leavens the grimness and the tragedies. Political points are made but not laboured and skilful editing(by Paul Sutorius) contributes to the sense of balance established by Gaylene Preston's sensitive direction. Bread and Roses maintains an understated, low key approach. The scene where Sonja helps lay out her first dead body, that of a young woman for whom an abortion has turned septicaemic, exemplifies this. From the perspective of a highangle camera, the scene is shot so as to distance the viewer and give the appearance of detachment. But the soundtrack and mise-en-scene are so 'true' that there is no need for viewer manipulation. You are moved because the event is moving. You cry because the woman's death, and Sonja's horror at seeing it, are genuinely affecting.

In its recollection of the experiences of New Zealanders during and just after the war years Bread and Roses acts as teacher (for those who weren't there) and prompt (for those who were). Given that in the current round of biopics entertainment value appears to have the edge on accuracy (as in Malcolm X and J.F.K., for example) it is a relief to many that the Bread and Roses team have opted for a concept that relies on finding a kind of 'truth' in their telling of the Sonja Davies/New Zealand story. And while no doubt there is room for the pedant to debate details of authenticity – Sunday Star correspondent Warren Drake, for example, complained (October 24) that 'The massive 135 tonne mainline Ka locomotive used in the Nelson railway protest scene was as out of place on the Nelson-Glenhope line as a Kenilworth semitrailer would have been on the backroads scenes of the series' – the production design (Rick Kofoed), sound (Kit Rollings), music (John Charles), photography (Allun Guilford, with Alan Bollinger and Leon Narbey as camera operators) and costume design (Chris Elliot) work together to recreate on screen, down to the finest visual and aural detail (the sound of baby suckling, the nurse borrowing the right gear for an appearance before Matron, the period props and costumes) the spirit of the story's times and places.

The Preston-Laing production team, established in 1984 when Gaylene Preston and Robin Laing combined their efforts to develop and produce Mr Wrong, goes from strength to strength. Their production of Bread and Roses, in association with executive producer Dorothee Pinfold, took seven years to develop and finance. Its first screenings were on theatrical release as a feature film. Financed by the New Zealand Film Commission, Beyond Distribution, New Zealand on Air, Television New Zealand and the 1993 Suffrage Centennial Year Trust, Bread and Roses is Preston/Laing's best work yet and, More Issues jibes notwithstanding, a wonderful suffrage year tribute to women of New Zealand.

ONFILM - Costa Botes

August 1993

EXTREMES OF ACHIEVEMENT

After the no-show of New Zealand features at last year's festival, locally made movies were back with a vengeance. Finance might be tight as ever, but any industry that can encompass the extremes of achievement seen in Bread and Roses and Desperate Remedies has to be in reasonable shape.

Artistically and technically, both films were world class. Desperate Remedies is a debut feature from the directing team of Peter Wells and Stewart Main. The benefit of their long filmmaking apprenticeship is everywhere apparent in the impudent assurance with which this startling, voluptuous work is crafted.

By attacking our prevailing notions of realism on a wide front, this overpowering southseas melodrama succeeds both as a provocative art-political statement, and as witty, sensual entertainment.

By contrast, Bread And Roses, Gaylene Preston's adaptation of the autobiography by Sonja Davies, has its stylistic feet planted firmly on the ground. But there's poetry in the ordinary everyday, and Preston finds it.

Warm, generous, and moving to a fault, this superbly mounted evocation of a life and an era slips through its epic length without a hint of a stumble.

The enthusiastic response by the local audience owes much to the film's dramatic strength, but much also to the welcome shocks of recognition with which we are able to greet all the vital cultural details imbedded in the narrative. I can only take up the common cry. Why don't we get more local drama like this?

Commercial imperatives may always rule the roost – we are, after all, a materialist economy founded as an exploitative colony – but the best reasons for having a homegrown film industry are all cultural.

As we move towards our third century, we have yet to fully debate, let alone resolve, the question of our national identity.

Cinema, produced by visionaries and storytellers gifted as those highlighted here, is a vital further step along that road. It also gives the rest of the world a window into our soul, putting a human face to an otherwise obscure, and perhaps highly dispensable blip on the edge of the map. Do take the opportunity then of seeing Bread and Roses in one piece, on the big screen. Many people did that during this year's Film Festival and were won over by the story's mix of nostalgia, politics, and engaging dramatic writing.

The scale of the achievement cannot be discounted. Preston and her collaborators have effectively put together the equivalent of two feature films. Logistically this is no mean feat.

That the finished result happens to be utterly confident, moving, and memorable is downright miraculous.

CAST

Sonja - Genevieve Picot

Charlie - Mick Rose

CREW

Director - Gaylene Preston

Producer - Robin Laing

Executive Producer - Dorothee Pinfold

Designer - Rick Kofoed

Editor - Paul Sutorius

Photography - Allen Guilford

Camera Operators - Alun Bollinger, Leon Narby

Music - John Charles

Script - Graeme Tetley and Gaylene Preston

Bread and Roses

by James Oppenheim

As we come marching, marching in the beauty of the day,

A million darkened kitchens, a thousand mill lofts gray,

Are touched with all the radiance that a sudden sun discloses,

For the people hear us singing: 'Bread and roses! Bread and roses!'

As we come marching, marching, we battle too for men,

For they are women's children, and we mother them again.

Our lives shall not be sweated from birth until life closes;

Hearts starve as well as bodies; give us bread, but give us roses!

As we come marching, marching, unnumbered women dead

Go crying through our singing their ancient cry for bread.

Small art and love and beauty their drudging spirits knew.

Yes, it is bread we fight for -- but we fight for roses, too!

As we come marching, marching, we bring the greater days.

The rising of the women means the rising of the race.

No more the drudge and idler -- ten that toil where one reposes,

But a sharing of life's glories: Bread and roses! Bread and roses!