1995, 94 minutes

In this moving documentary, seven elderly women recall their personal experiences of World War II. Their heartfelt tales have the capacity to move an audience to laughter and to tears, as they tell of love, death, small pleasures and large fears in a time of enormous change. From tragic love stories to long-suppressed revelations of sex and loss, War Stories is a richly revealing touchstone of New Zealand history.

“Gaylene Preston takes a simple idea

and turns it into a rich, universal experience proving that there is nothing more beautiful than the human face talking from the heart.”

Selected: Venice, Sundance, Toronto, London, Hong Kong,

Gothenburg, Munich, Melbourne, Los Angeles, Toronto, Montreal, Seattle, Chicago

You can buy / rent it online:

CONTEMPORARY WORLD CINEMA - Kay Armatage

Issue 175, 1995

It's always a pleasure to find a documentary that is gorgeously lit and shot in 35mm, complete with beautifully restored archival footage and a tasty Dolby stereo soundtrack. And when a documentary with such sumptuous production values brings with it wonderful characters, arresting stories, startling insights and new knowledge about another era, the pleasure transcends the merely cinematic and rises to another level. War Stories is such a documentary.

Simply constructed as a series of interviews overlaid with archival footage and personal photos, War Stories presents seven elderly women of different classes, races and cultural backgrounds speaking about the impact of the Second World War on their lives. Revelation follows revelation as Preston uncovers emotions long repressed by pain, smothered in shame, or disregarded as insignificantly personal in the context of the international politics of war. The candour with which all these women speak is astonishing from a group we tend to think has either not experienced or glossed over sexual passion, illicit love, heroic adventure, social ostracism, career fulfilment and painful death.

As the film progresses, the tales become more and more surprising, the emotions ever more deeply felt. Because the film is rigorously and specifically local, presenting a wide-ranging and reverberant portrait of New Zealand womanhood of the period, it points the way to a comprehensive new history. We could use films like this from every country, especially if they could all be as richly provocative as this one.

Principal Cast: Pamela Quill, Flo Small, Tui Preston, Jean Andrews, Rita Graham, Neva Clarke McKenna, Mabel Waititi

Director Gaylene Preston was born in Greymouth, New Zealand, in 1947. She started working in film in the seventies, while running a drama therapy programme at a psychiatric hospital near Cambridge, England. She returned to New Zealand in 1977, where she directed television commercials and several documentaries before making her feature debut in 1985. Filmography: Dark of Night (85), Ruby and Rata (90), Bread and Roses (93), War Stories (95).

Sponsored by GAP.

ILLUSIONS MAGAZINE - Laurence Simmons

Winter 1996

GUARDIANS OF AN ABSENT MEANING

Laurence Simmons reflects on the achievement of Gaylene Prestons' War Stories

'… when it's been bad, it's 'history' – and if it's been good, it's 'memories'.' - Tui Preston, War Stories

As a film that conveys the immediacy of the experience of the Second World War, as lived in New Zealand rather than on the battlegrounds of Europe, North Africa or the Pacific, Gaylene Preston's War Stories Our Mothers Never Told Us is entirely successful. Through a simple and hardly new (remember Reds…) technique of oral history interviews, the interviewee placed to one side of the frame and shot against a neutral black background, we effectively participate in the deep sense of loss of a new bride as not one but two ephemerally-shared husbands are declared missing in action. We wince at the awkwardness of reconciliation and the resentment of abandoned children upon the return of a long-absent husband or lover. We partake in the release of unbridled energy associated with the assumption of men's labour as women become 'manpowered' yet share these women's righteous indignation at the injustices of inequities in their pay and conditions. We are made to feel the scorching power of an event or a loss which has displaced a life, or may have ineluctably shaped and moulded it and the generations to follow, despite the fact that this is never played out as naked drama for us. Preston, along with women interviewees, refuses even the slightest hint of melodrama in her portrayal of the daily life of human beings and their difficulty in living in the world. It is in this sense that she profoundly respects the action of memory.

For what is unusual about War Stories is the responsibility of the filmmaker towards her represented subjects. Her film, as she has rightly pointed out in interviews, slides between the genres of documentary and drama: 'When I say the word 'documentary' I mean certain things. I don't mean reality programming, I don't mean infotainments, I don't mean exposé. I don't want to turn audiences into voyeurs and I'm not talking about 'personality' stuff. I'm talking about documenting life. I think there are plenty of feature filmmakers like me who like to document life.'

Preston understands that facts and fictions are intimately intertwined in any historical account and that because the documentary account can never exist outside of narrative it is not a merely neutral record of data, but is itself already textually processed by the culture in which it is produced.

While they are not free from error unconscious fabulation (especially fifty or more years after the events) the audiovisual interviews of War Stories allow spontaneous access to the resurgence of memory, as well as significant details of everyday life. As Claude Lanzmann's powerful film on the Holocaust, Shoah, teaches us, the more purchase we have on those events that seemingly escape us in the past. Walter Benjamin once remarked of the past that:

'All historical knowledge can be represented in the image of a weighing scale. One pan is weighed down by the past, the other by knowledge of the present. The facts assembled in the former can never be too numerous or insignificant. The latter may, however, carry only a few heavy massive weights.'

In the hype of our post modern lives we have made our negative definition of the ordinary assume typicality and a blandness and ignored the intensity and specificity of individuals' experiences and situations. Whereas it is really in this latter sense, according to Raymond Williams, that all culture is 'ordinary'.

Now that new information technologies can infiltrate and mediate everything, our search for the authentic, the unmediated experience, has become both more crucial and more desperate to our daily existence. In this 'society of spectacle' our technical expertise has allowed us to provide simulacra for almost any experience, however extreme or privately intimate that may be. However, the more technically adept we are in communicating or re-presenting our experience, the more seamless the interchange for soundbites, the more easily its effects are simulated, then the more interchangeable, the more forgettable that experience becomes. Who remembers last week's Hard Copy? In the aftermath of the Los Angeles riots it became clear that the Rodney King videotape played over and over again lost its expressivity, its metonymical power, as the idiom of its violence was routinised and viewers became anaesthetised to the cruelty and sensationalism of the event. In contrast, War Stories leaves powerful, yet often apparently trivial or irrelevant, images indelibly etched on our minds as we walk out of the theatre: 'The memory I have is clear today, silly little trivial things that you keep in your mind. A shoebox filled with three bunches of primroses and three bunches of violets,' says Rita Graham, recalling her one-year-old daughter's death. These images seem all the more true, more real, because we know that this is the way in which memory functions, evolving its own stories or symbols as a movie in our minds.

Today as we recede from the events of the Second World War, and those of us with first-hand knowledge of them dwindle in numbers, we are suffering from a sort of memory-envy, especially as the idiom of past violence is now played out again for us as a hideous parody in the concentration camps of Bosnia or French nuclear tests in the South Pacific. As Walter Benjamin was to lament in the early decades of the twentieth century, we have lost the ability to tell or listen to stories. Benjamin stresses the significance of a lack of awareness of finality, of temporality and consequently of mortality, to that lost capacity to tell and listen to stories.

Storytelling is intimate, it presupposes or anticipates the returned 'gaze' of the listener, but most importantly, Benjamin argues that storyteller's authority, his or her capacity to provoke recognition, stems from death itself: 'Death is the sanction of everything that the storyteller can tell' War Stories is an example of a new genre of the audiovisual which recuperates for us the function of storytelling: video-testimony. In the video-testimony the telling of the event is also a taking of responsibility for it and, despite the divide between past and present, video-testimonies express a much more difficult juxtaposition of temporalities than simple past and present. The facts of the past are not the only thing these witnesses seek to give, nor simply what we require from them. We are fascinated by their lives of 'afterlives': the way their daily reality is still affected by a traumatic past and may at moments shift back into it. This video-visual medium has its own hypnotism but unlike the simulacra, every time an oral history is retrieved in this form, it is as if video is employed to counter the numbering effects of video, to rouse our conscience and prevent oblivion. A good viewer notices the oddness, gaps, hesitations of voice, meanderings, non sequiturs, the apparently irrelevant details inseparable from the rhythm of memory, all the marks of the inexplicable in such a text.

In War Stories memory is allowed its own space, its own flow as the interview is conducted in a non-confrontational, non-interventional way, when the attempt to bring the memories of the past into the present does not simply elide all effect to the newer present – the milieu in which the recordings took place. Almost imperceptibly, significant events are brought to the surface and revealed: hidden lovers confessed to, misplaced desires acknowledged, a previously unremarked-upon victimisation proclaimed. If the incidence of so-called 'recovered memory,' our apparent ability to recover a deeper past through psychotherapy, seems to have increased dramatically in recent years, it may be that the images of violence in many different forms made manifest hourly on our television and cinema screens have popularised the idea of a determining trauma. So it is understandable that many might feel a pressure to find within themselves an experience that is decisive and bonding, the possibility of some terrible identity marking their lives. For it is equally true that the pain of an absent memory may be greater then the wound of a memory recovered.

Maurice Blanchot writes that 'to confess or to engage in self-analysis…in order to expose oneself, like a work of art, to gaze of all, is perhaps to seek to survive' Despite the fact that it provides access to the personal and the intimate, War Stories, as Preston insists, is not voyeuristic. This is because our gaze as viewer is never inveigled into a point of view, our imaginations never captured in a programme of thought. In this film the viewers' eyes area fully implicated in the imperative to make things visible. We are made aware of our detached and silent glance as spectators removed, yet under a spell, so close to voyeurism, we share the intimacy of each interview. This is also true because in the archival material the film draws upon so effectively, the director makes us aware of a structural gap that exists between the visual footage and the soundtrack voice-over. This familiar male authority voice drawn from many of the original National Film Unit Weekly Review segments is constantly ironised as Preston makes us laugh at the all-too-obvious clichés, cringe a little at the stageyness of the government propaganda machine, smile at the sentimentality of the songs on the soundtrack. In so doing, she poses the question what is an authentic depiction of the past? Is it to be found in the confident male voice-over's mythology or in the women's tangle of voices where the presence of the past is evoked primarily though human speech, through testimony?

War Stories, because it focuses on women's stories, exposes a set of questions concerning the stakes for masculinity's contemporary rememberings of itself. It undermines the pastiche of boy's own stories that characterised the recent television series New Zealand at War which, with its quickfire editing and relentless voice-overs, reflected an inability to enter history and a deep incapacity to acknowledge loss. This was an emotionally inadequate masculinity crisis marked , as Gaylene Preston has suggested of the official (male) story of the war. By 'that amnesia that blocks out thoughts of waste and futility and turns them into mythology' A sanitised, collective mythology that mourns a phallic masculinity of boys playing with guns in a nostalgic elegy for a lost, idealised father. War Stories ironises these constructions of masculinity and presents the other face of war: The surfeit of unwanted pregnancies, the difficult struggle of conscientious objectors, the government appropriation of ancestral Maori land, the lack of psychological support for returning soldiers. This face of war is a shadowy, haunting darkness, a mask in need of a soul:

' War took away the predictability of life, I am a fatalist now because I feel that covers up all the unpleasantness.' - Pamela Quill

'The war changed our family. Somehow it changed it from a nice happy family to a kind of remorseful family.' - Florence Small

'Wartime, especially, was a period of secrecy. The secret…it couldn't be talked about, and that's not me. I had to talk things out. I had to. And since I've been able to do that, nothing will frighten me again in my life.' - Rita Graham

In this film the one modality of memory Preston's women never engage in is nostalgia. If we were to seek for an equivalent literary figure for the film's mode, it would have to be prosopopoeia. A prosopopoeia is the giving of a face, a name, or a voice to the absent, the inanimate, or the dead. Many times this film gives that face literally as we focus on a still portrait photograph, creased with caring rather than glossy, of the missing person and listen to a woman speaking:

'He came into the room, and I just looked across at him. My heart started thumping, I felt sort of peculiar in the tummy, I felt weak at the knees. I though he was just the most marvellous-looking being I'd ever seen and hoped like mad that he'd ask me to dance.' - Pamela Quill

War Stories literally calls up the names of those who have gone, functioning in this way like the more concrete war memorials that are to be found in every small New Zealand town. The film also speaks to the fact that we live to be the survivors of the deaths of others and this is a determining feature of the human condition. If prosopopoeia is a coverup of death or of absence, a compensation, this is because its power is needed even in relation to our living companions who are always somehow absent even in moments of the most intimate presence. The film is memorial, compensation for a loss, as it must be for the women speaking, and in another more general way, for the viewers, it is an attempt to make up for the ultimate loss of death, ultimately our own deaths.

Maurice Blanchot is the contemporary writer who has written most willingly of death, memory, and forgetting while writing and thinking about the disaster that is war which haunts our century. As Blanchot says, the disaster belongs to a past that never ceases to impend. But how, he asks, can we talk about the disaster when by its very nature it defines speech and compels silence? How do we abide within its threat without abandoning the task to describe, explain, redeem and prevent again its pain? Paradoxically only by speaking. Blanchot employs the infinitive to indicate the timelessness of the interim, in particular the infinitive dire (to say, speak, tell). He nominalises and capitalises it as le Dire speaking, sheer telling as opposed to anything told or kept secret; the conviction that speech, not any particular communication, but the offering of language that makes Preston and the women interviewees of War Stories in Blanchot's phrase 'guardians of an absent meaning' For it is in their words we encounter the devastating responsibility of what Blanchot names as the last wish of those who suffered in the death camps:

'Know what has happened, do not forget, and at the same time never will you know.'

—

i) Gaylene Preston, 'Through Women's Eyes,' Interview with Stephanie Johnson, Quote Unquote, 25 July 1995, pp.14-17, [p. 15]

ii) Quoted in Irving Wohlfarth, 'The Measure of the Possible, The Weight of the Real and the Heat of the Movement: Benjamin's Actuality Today,' New Formations 20, 1993, pp.1-20 [p.11]

iii) Raymond Williams, The Long Revolution, London: Chatto & Windus, 1961, p. 37. iv) The work of Guy Debord and Jean Baudrillard has examined the formation of these simulacra in some detail.

v) Walter Benjamin, 'The Storyteller: Reflection on the Work of Nicolai Lesov,' in Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, translated by Hannah Arendt, New York: Schoken Books, 1968, 9.94

vi) The Writing of the Disaster, translated by Ann Smock, Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1986, p. 64.

vii) Gaylene Preston, Preference to War Stories Our Mothers Never Told Us, edited by Judith Fyfe from a film by Gaylene Preston, Auckland: Penguin Books, 1995, p.7.

viii) In particular his The Writing of the Disaster, op. cit., and his earlier essays 'Forgetting, unreason' and 'Forgetful Memory' in The Infinite Conversation, translated by Susan Hanson, Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 1993, pp194-201 and 314-317; as well as the 'Essential Solitude' in The Gaze of Orpheus and Other Literary Essays, translated by Lydia Davis, edited with an afterword by P. Adams Sitney, New York: Station Hill Press, 1981, pp63-77

xi) Blanchot, The Writing of the Disaster, op. cit., p. 82.

LOS ANGELES TIMES - Kevin Thomas

7 June 1996

NEW ZEALAND WOMEN TELL MOVING 'STORIES' OF WAR

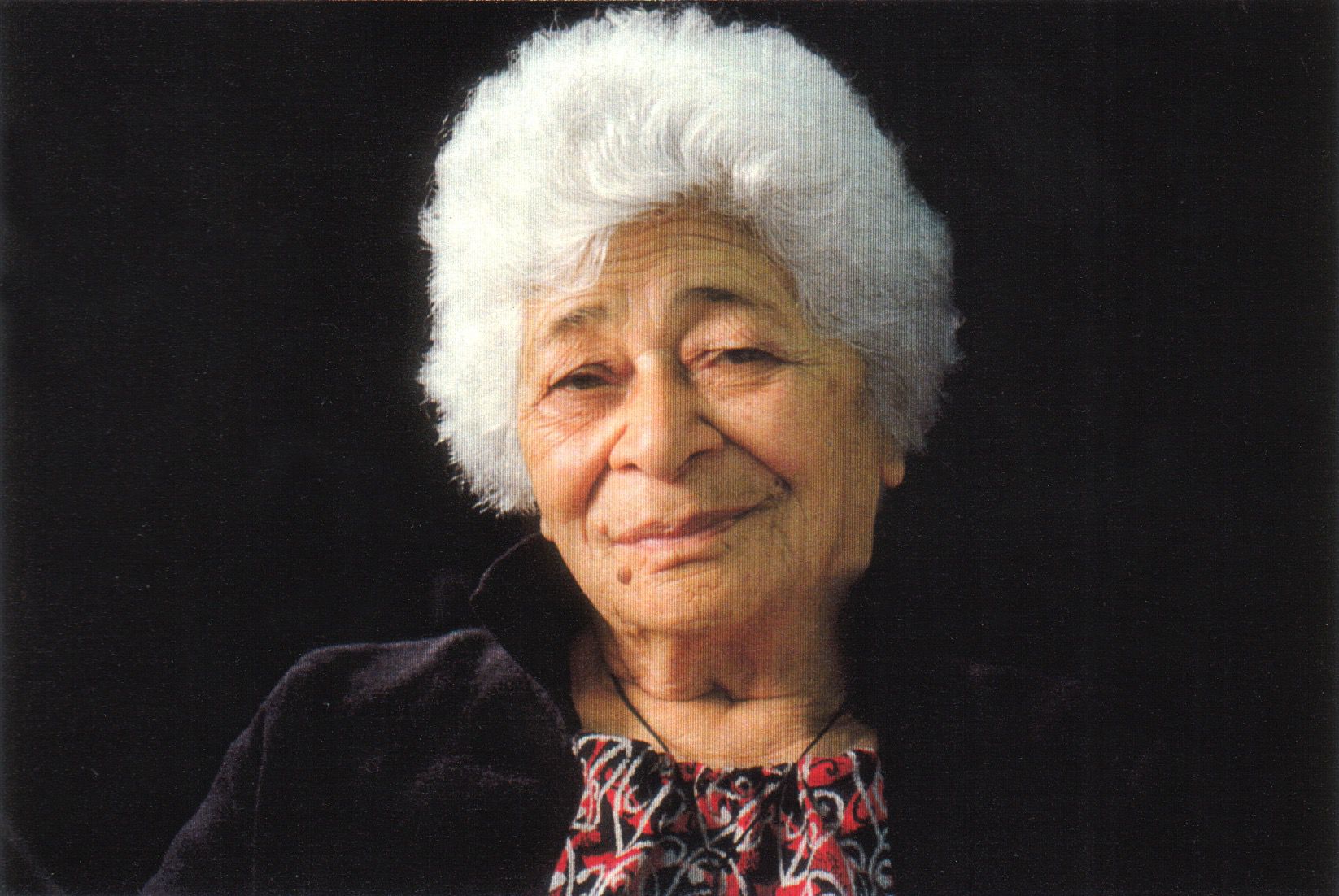

In her prize-winning documentary WAR STORIES Our Mothers Never Told Us, New Zealand filmmaker Gaylene Preston takes a simple idea and turns it into a rich, universal experience. She has gathered seven elderly women, seated them one at a time in front of a black dropcloth, and asked them about the impact of World War II on their lives, while interspersing archival footage and stills. There are many levels and meanings to what skilled off-screen interviewer Judith Fyfe draws from these pleasant, grandmotherly women. Right away Preston and Fyfe remind us of how easy it is for it not to occur to us that ordinary-looking people could ever have had extraordinary experiences. Yet these women are full of alternately warm, romantic, harrowing and tragic tales. Preston's film inevitably provides a fresh perspective on the World War II era. The United States and New Zealand were – and are – so much alike in many ways. Both countries sent their young men to distant locales, both have puritanical traditions, but New Zealand, which had a population of only 1.5 million when war broke out, is so much smaller, so much more remote and even now so much more conservative. What we hadn't expected to learn is how strong and deep anti-American feelings ran among New Zealanders at the onset of war, and Preston, in addressing her own people primarily, never tells us why.

Two of the women are Maori, and one of them became an honorary U.S. Marine for her service as a kind of mother figure for an American military camp, where her informal duties extended far beyond washing and ironing uniforms. By and large this woman, Jean, has good things to say about Americans, but she does report putting a racist in his place.

The other Maori woman, Mabel, tells of taking over her family's school bus and trucking business while her husband served in the Maori Battalion, which suffered great losses.

Throughout, Preston's researchers went to considerable effort to provide specific contexts for their interviewees' recollections, and the newsreels of the returning Maori soldiers and all the traditional ceremonies involved are especially memorable.

Preston's women all have such striking, often painful revelations that they shouldn't be given away here. (One woman, for example, tells of her own devastating frontline experiences in Egypt and Italy.) Inevitably, they involve losses but also various forms of discrimination and, at times, an oppressive conformity.

Ironically, in this light, one woman, who is in fact Preston's own mother, tells of an unhappy wartime marriage she had a special reason for not forsaking and what it cost her to make work.

There are lots of things we don't learn about these women we've come to care about. Are those whose husbands survived the war still alive? What about their children and grandchildren? But that's not what War Stories is about, and Preston has made a succinct, captivating 95-minute movie that perhaps wisely leaves us wanting more.

WAR STORIES DVD RELEASE - Helen Martin

Women in Film and Television 2005

'It felt like I stumbled onto a beach that I'd kind of lived on all my life and I stopped for a minute and I turned over a stone and there was treasure. And I was lucky enough to be surrounded by the right people to support a process that meant that I could capture that stone in light and plastic and beam the message out.'

- Gaylene Preston, commentary in conversation with Judith Fyfe, DVD War Stories: Our Mothers Never Told Us, 2005.

The contribution film makes to a culture is immense, perhaps nowhere more sharply focussed than in stories told through the documentary form. And when a documentary is supported by a body of work in other media, its cultural value is exponentially increased.

The DVD release of War Stories: Our Mothers Never Told Us in time for the 60th anniversary of the end of World War 11 is cause for much celebration, not just because the re-release of this superb film draws new attention to it, but also because it carries material that adds more layers to the story thus far told via an oral archive, an exhibition, a book with expanded interviews and, of course, the original 7-interview film.

To briefly reintroduce the work – War Stories began as an idea during research for the docudrama Bread and Roses when, unable to initially get funding for a film, Gaylene Preston, with initial funding form the Lotteries Commission and the Suffrage Centennial Fund, organised interviewers to find out from 66 elderly women the spectrum of their experiences during World War 11. On a personal level Gaylene was inspired to seek out the 'secrets' of her own mother Tui's story when, in 1986, Tui commented that the theme tune from Casablanca was special for her 'because of the war'. From those initial interviews, eight of the storytellers two years later re-told their stories on film and seven of the interviews, intercut with stills and archival footage and accompanied by the Casablanca tune, formed the basis of a documentary that has gained both critical and popular acclaim.

Chief interviewer, journalist Judith Fyfe, came to the project not so much interested in World War 11 as in working with Gaylene collecting oral histories, or 'what isn't published'. This interest had led her, with Hugo Manson, to set up an archive, now housed at the Alexander Turnbull Library, to record the stories and voices of New Zealanders.

On the DVD's commentary track Gaylene and Judith talk as the film plays, their conversation ranging widely through issues of interview techniques and protocols, the small details and the big picture of social and cultural mores during World War 11, the contributions of the women who eagerly agreed to tell stories that had never been told before and their own learning resulting from the project. They discuss how oral histories 'look at the edges of the frame', Gaylene's anxiety that, before all the interviews could be done 'someone was gonna die' and the beauty of Alun Bollinger's cinematography. It's a rich and fascinating resource, adding so much depth and texture to our understanding of the War Stories women, the events, the emotions and the ideas they so eloquently describe.

Also a fantastic DVD bonus are an eighth interview, shot at the time of the others but only released now that the subject, artist Doreen Blumhardt (now 92) has decided it's time her amazing story sees the light of day, and a featurette showing the seven original participants in Hollywood for a triumphant US cinema release.

CAST

Pamela Quill

Flo Small

Tui Preston

Aunty Jean Andrews

Neva Clarke McKenna

Rita Graham

Aunty Mabel Waititi

CREW

Producer/Director - by Gaylene Preston

Executive Producer - Robin Laing

Cinematographer - Alun Bollinger

Editor - Paul Sutorius

Music - composed and arranged by Jonathan Besser

Interviewed by - Judith Fyfe